Bored and border

When the inbox won't let you out

I didn’t mean to attempt to sneak past the border. But the military area to my left was entirely enclosed by a metal green fence, and I couldn’t see anyone moving between the buildings inside. The booth directly before me seemed much likelier to enclose someone who could process my passport, and the path ran past it straight down into Kyrgyzstan.

So I cycled up to it and, seeing no one inside, thought to try the next one along. A shout stopped me, and a soldier with a large gun was angrily waving me back. I met him at the gate. He yelled at me for a few moments in Russian, rifle dangling over his shoulder, anger in his eyes. “Passport,” he said. “Passport!”

Not the best start to breaching the border. He took my passport. “Tourism Minister?” he demanded, referring to the email you currently need to send in advance so that the Ministry for Tourism can grant the army permission to let you through. Yes, I said, I sent it. He stomped back inside the fence, and I began my wait.

I was attempting to pass at the Khyzyl Art border. I had heard bad things about it. Passing between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan is sensitive at the best of times, and the two countries were still recovering their relationship after fighting in September 2022 killed nearly 40 civilians and displaced more than 130,000 Kyrgyz people. Both nations have since been accused of war crimes by Human Rights Watch.

Those skirmishes occurred at a section of their border in the Ferghana Valley, close to Uzbekistan, which has been a particularly complex area since the fall of the Soviet Union left the Central Asian republics to negotiate their borders between themselves. The early years of the USSR saw some border demarcations made, largely along ethnic lines. The mixture of cultures throughout the region made this impossible to do perfectly, leaving territorial tensions existing between most countries in the area today. Occasionally, these flare into fighting.

This border is the furthest crossing from where that fighting took place. It is a beautiful boundary which shows the silliness and arbitrary nature of national borders: here, amongst high mountains which were still spread thick with snow in late summer, were a Tajik and a Kyrgyz military outpost, 20km and 1000m of altitude away from each other.

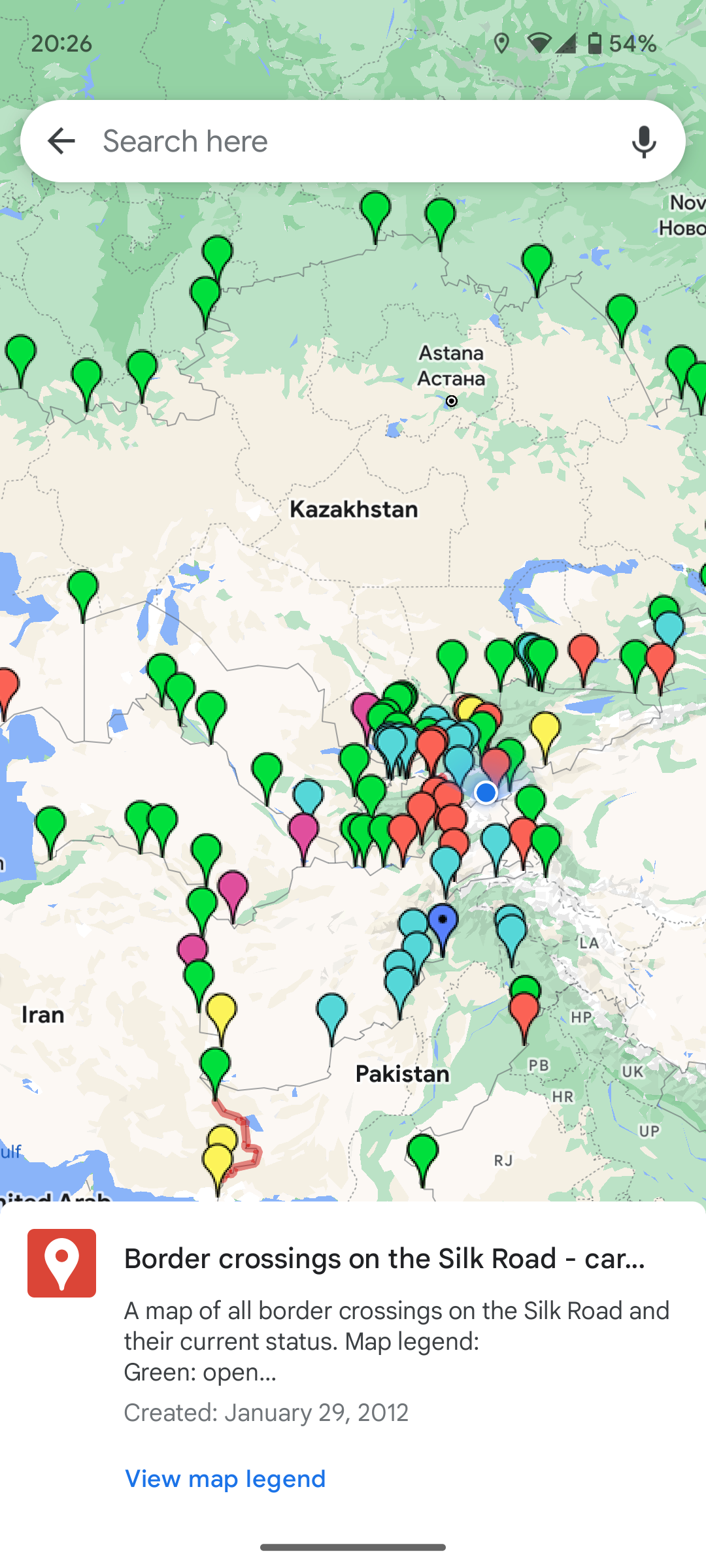

It’s an immense irony that travelers in Central Asia, a region known for the prevalence of nomads, are obsessed with borders. But they have to be; they overlap in such strange ways and have such constantly changing statuses, and such regularly evolving visa conditions (which may or may not always be understood by the people working at the borders) that they are a regular theme of discussion. These borders often shape people’s trips, including mine. I had not planned to travel along the famed Pamir Highway until I arrived in Osh, where I met a German man who had just crossed Khyzyl Art from Tajikistan to Kyrgyzstan.

Further accounts online corroborated this. The popular Central Asian travel site Caravanistan had a forum specifically dedicated to tales of tackling this border, which in a matter of days went from disappointed British backpackers bearing bad news from their embassy, to two Polish hitchhikers who seem to be the first who made it through. Since then, successful accounts continued to trickle in, providing advice for what to do. Simply send the Ministry for Tourism a picture of your passport, tell them when you want to cross, and voila.

Not so for me.

The soldier returned to the fence. He still seemed angry and asked me something in Russian, pointing at a calendar. What date had I sent the email? August 12th, I replied, realising with a sinking feeling that was a Saturday, and today only a Monday.

“Nyet!” he yelled, crossing his arms. They don’t work on Saturdays! Of course they don’t work on Saturdays! He disappeared again.

A different officer came out around an hour later. He had a friendly face and smoked long cigarettes and carried no gun. I offered him some peanuts, which he gratefully accepted. “We have found your email,” he said through Google Translate. “Now you must wait for the letter. It will come maybe after dinner, or tomorrow morning. Do you need anything? Food or water?”

I didn’t. I just needed the goddamn letter which, it seemed to me, shouldn’t be that hard to do if the Ministry for Tourism already had my email. Just adding my name to a template and pressing send, no?

No, apparently not. Couldn’t the officer call anyone? No, apparently not. He gestured to a grassy area nearby. “Palatka?” he said. Yes, I have a tent. He pointed to the other side of the border, about 100m away, where a man stood in a red jacket. “Francia,” the officer said, shrugging. He was in the same situation. We waved at each other. There was nothing to be done for us. We just had to await the letter. The officer thanked me for the peanuts and left.

I settled in. For the first five or six hours, I still had some hope I might make it through that day. And, truthfully, I initially wasn’t too resentful. I had been pushing myself hard for days cycling the Pamir Highway, regularly choosing to forego early, relaxing afternoons in exchange for more miles. I worried a little that my haste had decreased my appreciation for the range I had been riding through, that maybe I’d missed out. With the border still embedded in the mountains, perhaps this was the world’s way of forcing me to be still with them for a few moments more.

This bliss sank with the sun and I grew cold and frustrated. The door to what seemed to be their main office occasionally opened with the wind; each time I looked up in hope that it would be the officer coming out to welcome me through. It was not. Other travelers came through, their letters already sent, and they were let in. Cows came wandering down from the nomads’ encampments further into the mountains. One pushed the gate open with its nose and walked in to graze on the grass.

Cows could get in, but not me.

I waited more. The day darkened to twilight. The glaciers lost their glisten. A soldier walked up to the gate purposefully: was this it? Would I still have time to make it to town, a guesthouse, a bed? But I caught myself. “It’s as likely to be about the cow as anything else,” I thought. I was right. He let the cow out and walked back without looking at me. The cow walked into Kyrgyzstan happy and free.

The Frenchman put up his tent and so did I. We waved to each other. We did so again in the morning. At around 9am, the officer appeared again, holding up Google Translate on his phone screen: “You will wait for the letter.”

Yes, I know I will. For four more hours I did, until it had been 26 hours since I arrived there and tried to sneak in. But suddenly, the officer barged out of his office yelling “Francia! Australia!” and waving me in. A cursory glance and a quick stamp of my passport, and I was free, ecstatic at the border being behind me. I flew down the road into Kyrgyzstan, the great snowy mountains somehow looking more magnificent, the roaming horses more majestic, the green fields fresher and more fertile than before.

An email from the Ministry for Tourism awaited me when I got back to wifi. “Yesterday I sent a letter to the border service,” it said. “They will let you pass.”

Yesterday? That meant the letter had been accessible the whole time, ready to go, while I waited to enter a country in which I had already been two weeks before, held back, apparently, only by soldiers who didn’t know how to refresh an inbox.

I laughed. Despite the delay and the hassle, I felt fine. Maybe those extra hours spent lying on the grass, reading, looking up at the glaciers and sharing peanuts with the army weren’t entirely wasted. After all, I’m here to experience Central Asia, and borders are, for better or worse, a big part of that. Even if only to sometimes make you slow down.

Just don’t try to sneak through.

Please less soldiers with guns in the future!

Jake, love your writing, not sure it is your father or mother you follow, but keep it up. Beth